A History of Brussels Beer in 50 Objects // #46 Papy Van De Pils Label

Object #45 - Papy Van De Pils Label

21st century

Brewery Life

Find out more about Brussels Beer City’s new weekly series, “A History Of Brussels Beer In 50 Objects” here.

In 2018, a strange fever took hold in Brussels. It was not a new affliction, but when bacillus responsible last reared its head, it introduced a brewing monoculture that doomed breweries like Leopold, Vandenhuevel, and Roelants to oblivion. Three decades after Wielemans brewed their last bottom-fermented beer, Brussels’ brewers had started making Pilsners again.

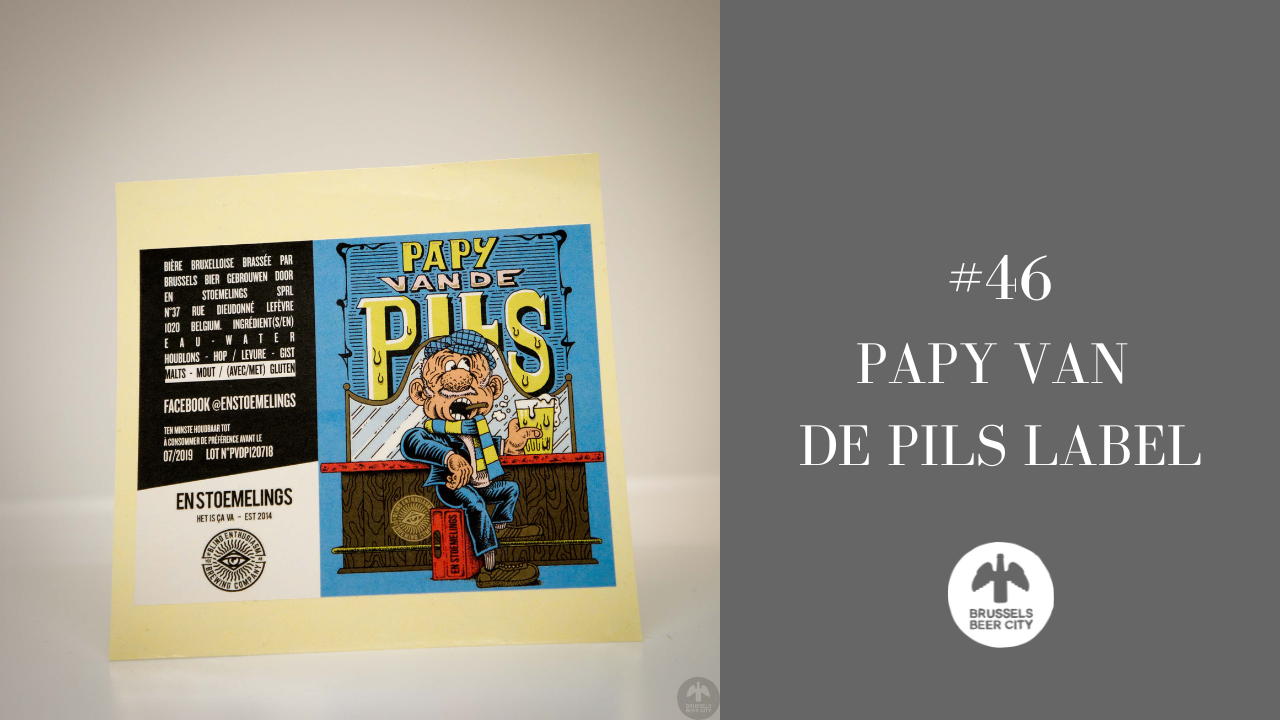

The first inklings of Pilsner fever’s return came in November 2017, when Nanobrasserie L’Ermitage released an exotically-hopped Lager, and followed it up in spring 2018 with a New Zealand-hopped beer for their experimental Laboratoire d'alchimie series. These were both one-offs, but more perennial Pilsners were just around the corner. In mid-August 2018, Brasserie En Stoemelings announced they were releasing a new Pilsner - Papy Van De Pils - as a festival exclusive for the forthcoming BXLBeerfest.

Papy was the brewery’s first bottom-fermented beer, and their first collaboration (with Blind Enthusiasm Brewing from Edmonton in Canada). It was a light-blond-verging-on-straw beer, bitter, slightly malty, light and refreshing - an Echte Pils (“real Pils”) according to En Stoemelings, one which provoked publisher of the now-defunct Belgian Beer and Food Magazine Paul Walsh (no relation) to call it “a…beer that captures everything that’s good about beer.” A scant two weeks later and Brussels Beer Project were at it, trumpeting a new crowd-sourced core beer called Wunder Lager, a 3.8% hoppy Pale Lager featuring a combination of very un-German Cascade, Citra, Columbus and Mosaic American hop varieties.

Confirmation - if it were needed - that Plisner was becoming endemic in Brussels came the following year, on December 5 2019, when Brasserie de la Senne announced the arrival of Zenne Pils. A German-style Pilsner, its development was aided - thanks to the input of the brewmaster at the Schönram brewery - by Bavarian brewing knowledge, just like its early-20th century predecessors.

It was inevitable that Brussels would succumb to the Pilsner bug. Brussels (and Belgium) has been Pilsner country ever since the style arrived here. The drinkers and brewers alike still consume it in large quantities, making it a lucrative market for the canny breweries able to crack it. There remains a stubborn nostalgia for the well-made Pilsners of Brussels’ post-WWII industrial breweries - witness Brasserie de la Senne name-checking Wiels of Wielemans and Vandenheuvel’s Ekla when they launched Zenne Pils.

All it needed for Pilsner to reappear in Brussels was for this new generation of brewers to gain enough confidence at the mash tun to take on the sometimes-unforgiving process of brewing well-made Pilsners. When they did, it wasn’t the commodified Pilsner monoculture of their 1950s predecessors that they recreated. Instead, there emerged a diversity of strains, some, like En Stoemelings, de la Senne, and L’Ermitage - who introduced their core range 81 Express Brussels Pilsner in January 2020 - who leaned towards the traditional. And others that exhibited a more pronounced New World influence, represented by Wunder Lager and beers like La Source Beer Co.’s Sour Pils or tropical India Pale Lager.

Either way, after a 30 year interregnum, Brussels was becoming a Pilsner town once again.