Catch a falling star // Expo 58 and the flameout of Brasserie Vandenheuvel

1958 was a landmark year for Brussels, and an inflection point for the city's breweries.

For six months, all of Belgium descended on the city for the Brussels World Fair, and the city’s brewers stepped up to supply them with as much beer as they could handle. Expo 58, as the fair was known, was the coming out ceremony of a modern, confident Belgium. And beer was central to this; the city’s breweries had transformed an artisanal craft into an industrial behemoth ready to conquer Europe.

But, just as the Expo proved to be a false dawn for this now Belgium, so it was for Belgian breweries, a fall from grace exemplified by Brasserie Vandenheuvel of Molenbeek, the “star of the expo”.

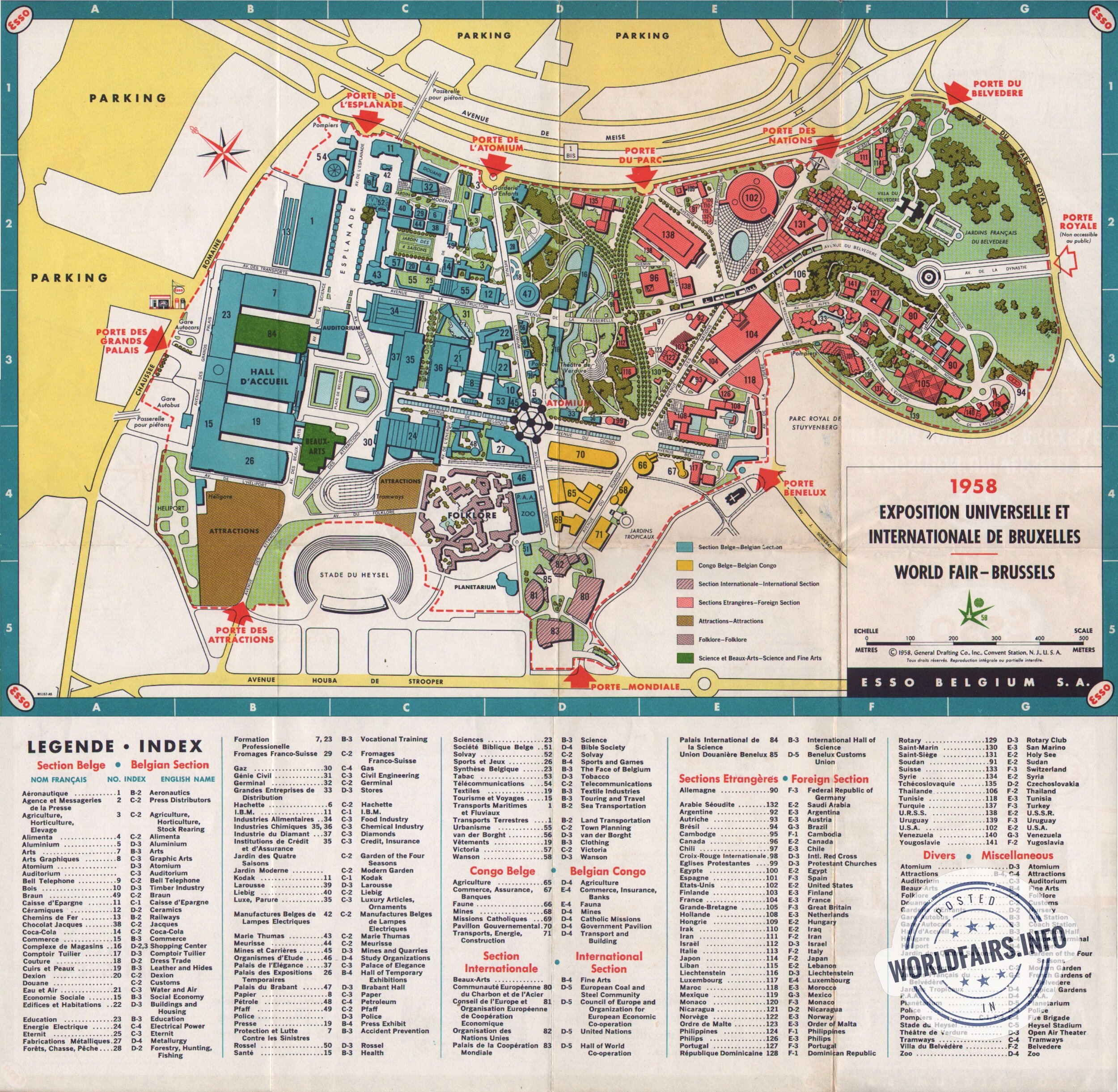

Expo 58 represented “the last moments of a prosperous, joyful, carefree, colonial and united Belgium.” Opened in April 1958 on the Heizel plateau, the fair rode the wave of 1950s post-war optimism, showcasing new technologies and the wonders of the new consumer economy, across 200 hectares and 44 country pavilions. Everywhere you looked, there was beer.

In the Expo’s centrepiece, the Atomium, visitors could sit in a restaurant in one of the structure’s chrome balls and have a glass of Vandenheuvel’s Ekla Pils with their dinner. The “star of the Expo”, Ekla was everywhere. It was Vandenheuvel’s big shot at national success and a culmination of 100 years of brewing success.

From Saint Michel to Vandenheuvel

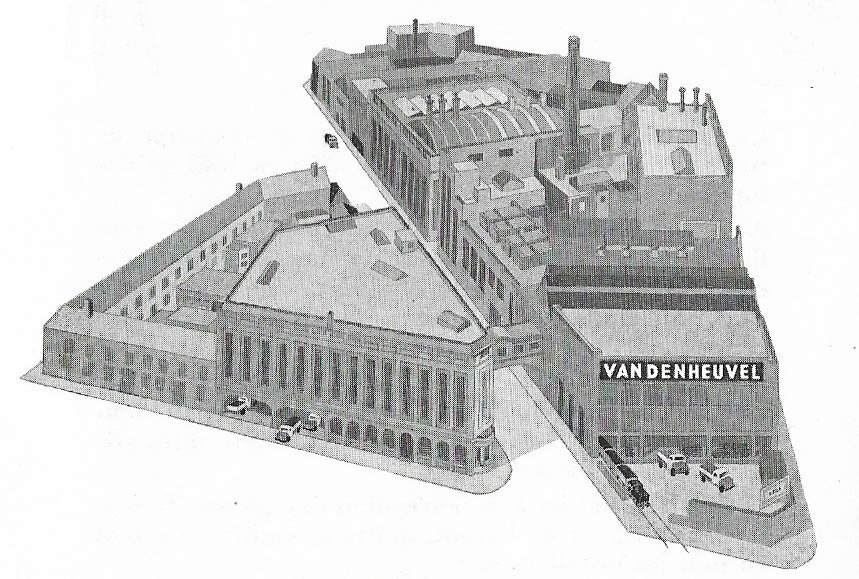

Vandenheuvel’s origin is standard Brussels brewing history. The brewery started out in the centre of Brussels in the 1840s as Brasserie Saint Michel. Under director Henri Vandenheuvel, it grew quickly, being the first Brussels brewery produce dark, Bavarian-style beers. That success led Vandenheuvel’s successors to expand the brewery – now rechristened – at a 40-acre site across the canal in Molenbeek in 1920.

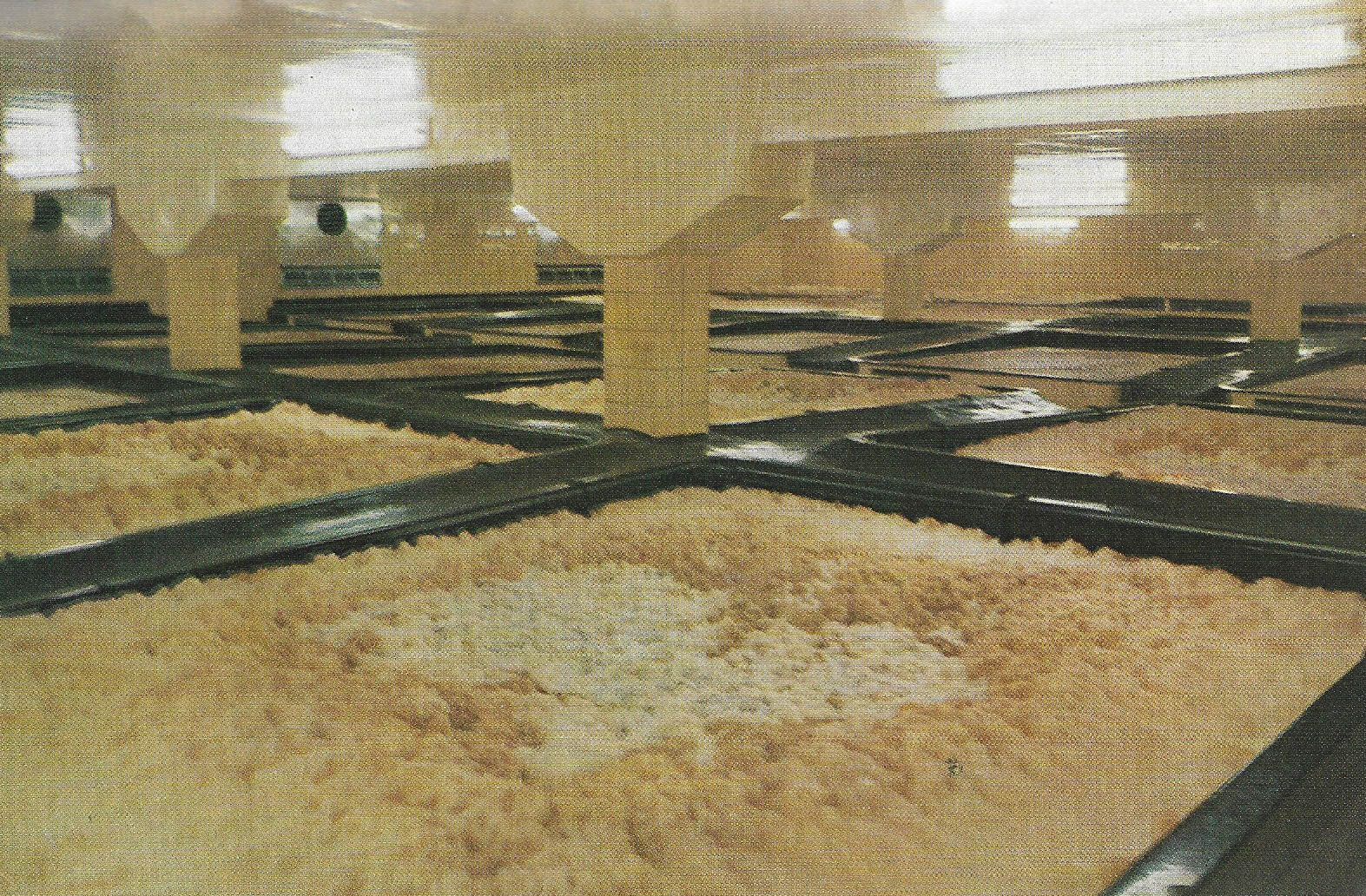

Over the next 15 years, Vandenheuvel built a massive new brewery and introduced new beers: a stout, a bière de mars, and later pilsners, and Munich beers. By the mid-1950s, as Expo 58 hove into view, the Vandenheuvel brewery had tank space for 10 million litres of lagering beer fermented in vast open-topped tanks, and could package 45,000 bottles an hour. In 1958, the brewery's output was focused on Heizel.

As part of the Expo, a folksy Belgian village was built, a comfortingly familiar sight for visitors arriving, and a way to send them home happy and well oiled with beer on the way out. In La Belgique Joyeuse – Happy Belgium – winding medieval lanes led onto baroque town squares flanked by renaissance town halls, behind which were streets lines with replicas of Belgium’s art nouveau architecture. The streets and squares thronged with accordion players, magicians, singers, and organists.

Happy Belgium, happy brewers

In return for financing the village, a cartel of 32 Belgian breweries drew lots to receive one of 40 cafes where they could sell beer to the Expo’s multitudinous crowds. Seven of these 40 served Ekla, from the Café William Tell, to the Cabaret Le Diable au Corps, and the Café Uylenspiegel. If you didn’t fancy an Ekla, you could trot across to the café of their local rivals Ixelberg for a half litre of Helles XL.

For the more curious drinker, the national pavilions of other beer-making countries had plenty to offer. Pilsner Urquell on the terrace of the Praha Restaurant. Whitbread’s specially-brewed Britannia Bitter at The Britannia Pub in the UK pavilion. Waiting for you at the base of the Atomium were freshly poured ceramic mugs filled with Dortmunder Actien Brauerei beer.

By October 1958, 80% of Belgians had visited the Expo, and La Belgique Joyeuse welcomed 4.5 million revellers. However, like the artifice of woof and plaster that was this Potemkin village, Expo never delivered on its promise for Belgium or for Vandenheuvel.

The village was bulldozed, and the pavilions dismantled. Belgium ceased to be a colonial power in 1960 on Congolese independence. Already simmering language tensions between the country’s constituent communities curdled in the 1960s, erupting periodically into unrest. Brussels was irrevocably transformed into a car-choked city.

A Falling Star

For Belgian brewing, the fate was even worse. Within a decade, many of the participating breweries disappeared unable to compete, or avoid industry consolidation. Vandenheuvel kept their head above water longer than most, absorbing some of its Brussels rivals in the late 1960s before being bought out by Watneys of England. Citing Ekla’s poor sales, Watneys shut down Vandenheuvel in December 1974. Save for an abortive attempt to revive the Ekla brand in the 2000s, Ekla was finished.

Coming like a ghost town

Visiting Heizel now, the Atomium still dominates – even if you can’t get a beer inside it anymore. Where La Belgique Joyeuse once stood is now the home of another ersatz tourist attraction – Mini Europe. Taking the curving tracks in the surrounding parkland, the rest of the plateau has been so denuded of Expo artifacts it’s hard to imagine where the vaulting pavilions of glass and concrete once stood. In the place of The Britannia pub is now a clump of trees framed by rolling, grass hills.

Elsewhere, Expo ghosts do still linger. In an esplanade, scarred by age and neglect, that once soared between sections of the Expo but now ends in a chequerboard viewing platform. Or the American pavilion, a UFO crash-landed o the margins of the Expo site and recycled as a now-defunct theatre.

From the top of the Atomium, looking southwest you might make out in the distance the site of the Vandenheuvel brewery in Molenbeek. It has fared even worse in the intervening years. The brewery was largely demolished once it was closed down. All that remained for a long time afterwards was a gaping hole in the ground where the brewhouse once stood, and an adjoining triangular building with the letters “VANDENH U ”.

The building is slowly disintegrating, and a skybridge that once connected it with the brewery hung loose in the air at one end for years. Now, though, freshly sandblasted, this bridge connects to new apartment complex emerging from the brewhouse crater. The, development is capped by an 18-storey apartment block, dwarfing the buildings around but keeping Vandenheuvel’s legacy alive.

Its promoters have christened it Ekla.