Mystic River // The Zenne Valley reckons with Covid-19 - Part I

The Zenne river’s entry into Brussels is hardly glorious. It slithers out from underneath the concrete cooling tower of a gas-fired power station into a grubby industrial estate that demarcates Flanders from south-west Brussels. It’s surprising to see the river above-ground at all. In 1871, tired of the repeated cholera outbreaks borne by the Zenne’s polluted waters, Brussels politicians celebrated the completion of a massive public works project to bury the river forever under the city’s streets. Brussels was born on the Zenne and grew powerful thanks to the connection it provided the city to the outside world. For centuries the river had also supplied the city’s breweries with fresh water, and its forced disappearance in the 1860s and 1870s was calamitous for Brussels’ brewers.

On the 150th anniversary of the vaulting of the river, Brussels and the Zenne valley are again in the throes of a deadly pandemic, one that killed 28,566 Belgian residents. Unlike the cholera outbreaks of the 19th century, Covid-19 is airborne, but it has the potential to wreak just as much damage on the region’s breweries.

How much damage exactly, I decided to find out. In early January and February 2021, with Belgium suffering through a second lockdown in nine months, I walked the length of the Zenne from Lambic’s reputed origin in Lembeek to Brussels’ new brewing district in Laken, speaking with brewers and business owners to find out the state of brewing in the Zenne valley in this strange time. Originally, this was intended as a contemporaneous account but it (and me) fell victim to lockdown-induced fatigue.

Which is why it is only appearing now, a year later. Instead of an on-the-ground report, it functions more as a snapshot of a particular moment when we didn’t know which way the pandemic was going to go. Which seems grimly appropriate as we wait in January 2022 to see which way the Omicron wave will break.

*

Lembeek

“Do you see that sign there? Over there, the blue one. We put that in. To help the tourists.” Karel Boon is standing at one end of a stubby concrete bridge, pointing to a small rectangular blue sign featuring three white waves and the word “Zenne”. We’re on the outskirts of the Flemish village of Lembeek, once home to 24 distilleries but now better known in drinks circles as the home of the Boon brewery. The Boons brew Lambic, the spontaneously-fermented wheat beer indigenous to the Zenne valley, the complex flavours and tart, funky character of which are the result of a a protracted brewing process and the unusual way in which the beer in inoculated with yeast, Unlike conventional beer, where the brewer adds yeast himself, in Lambic the fresh wort is inoculated by bacteria and yeast living in the air as it cools overnight in an open tank (known as a coolship), and in the staves of the wooden barrels in which Lambic fermentation takes place.

It’s a complicated, anachronistic way to make beer that is rare outside of the Zenne valley, and since January 2021 Karel and his brother Jos have taken full charge of Boon’s production following the retirement of their father, and the brewery’s founder, Frank Boon. Frank started his own Lambic blendery in the 1970s when Lambic was a tradition in terminal decline. Bucking the downward trend, he was eventually able to move outside Lembeek and build the brewery that now straddles the river. On one side, in an old industrial building abutting an elephant’s graveyard of decommissioned barrel staves and rotting electronic equipment, is one of two foeder halls, home to some of the brewery’s 161 wooden barrels capable of holding thousands of litres of maturing Lambic.

On the other side, facing onto the high-speed rail line to Paris, is the brewhouse, cooperage, and the Boon’s redbrick family home where Karel grew up. Frank is officially retired now, but as Karl and I cross the bridge heading to the foeder hall, we can hear him behind us busily repairing some barrels in the cooperage in his new, emeritus position as “head cooper”.

It’s cleaning day for the foeders. Brewery employees lug brightly coloured hoses from one barrel to the next as steam blooms out of holes in the wood before condensing in the morning chill into gloopy pools on the rough concrete floor. It’s a bit of a novelty for Karel to have staff on-site. Pandemic-related restrictions meant that for much of the preceding winter it was only him, his dad and his brother coming to work. “For two to three weeks it was very strange,” Karel says of the downsizing of their 20-strong workforce to just three. Another effect of the rolling lockdowns throughout 2020 was the evaporation of Boon’s on-trade business, but Lambic brewing’s long production cycles - measured in years and decades rather than weeks and months - insulated Boon a little better than some of their colleagues running conventional breweries.

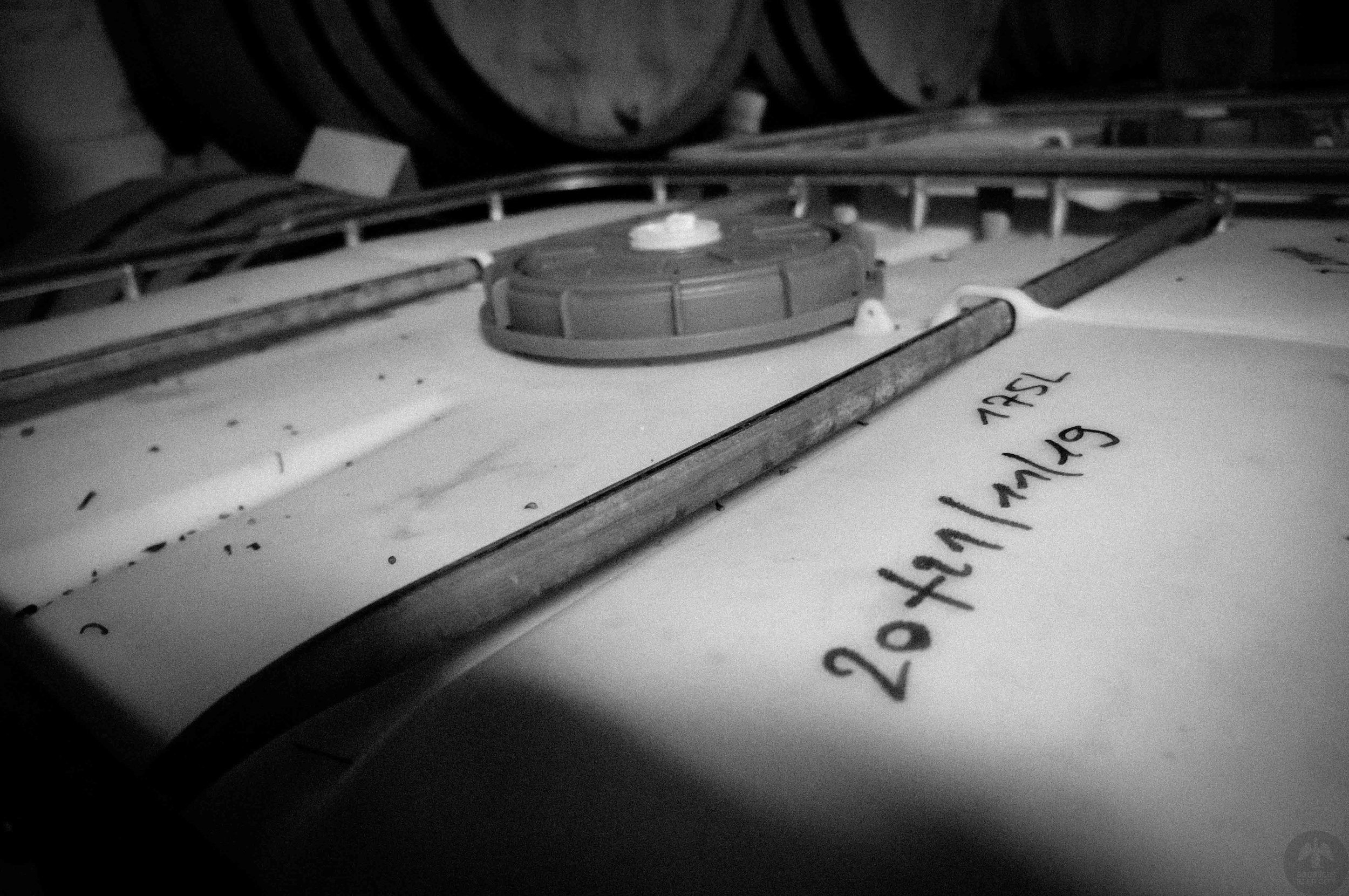

Once brewed, Boon Lambic spends between one and three years fermenting and ageing in a foeder before being blended to make Geuze or macerated with cherries for Kriek. Walking through a barrel canyon, Karel points out their oldest foeder - number 79, bought from a now-defunct Brussels brewery in the early 1980s and built in 1883. 62 of their foeders predate World War I, and Karel says it can take at least 10, and sometimes 15, years before a foeder really starts to produce a Lambic of sufficient quality. Each barrel is different, and the distinct character they lend to the Lambic contained within them is carefully noted by Karel, Frank and Jos in a spreadsheet dating back over 20 years. Number 79 from 1883 “produces fantastic Lambic,” Karel says, particularly suited to the brewery’s Mariage Parfait, a higher-strength Lambic and multiple World Beer Cup gold medallist. Boon’s foeders can hold around 22,000 hectolitres of beer, enough Lambic - and some to spare - to produce the two million bottles currently held in their storeroom.

Thanks to the pandemic the storeroom is fuller than usual. Production levels dropped as demand ebbed and their unsold stock increased, and the brothers used this downtime to install some new brewing equipment and plan for the year ahead. There was the matter of Frank’s retirement, for one. Marked by the release of a limited edition Geuze blend, called Apogee, for Karel the handover when it came was a natural evolution for the business. “We've been around the brewery since we're toddlers…[And] for me, the beer was just something natural in life,” he says, even if he was originally reluctant to get involved until having his head turned at beer festivals where he saw first-hand the reaction his father’s beers elicited in drinkers. “The fact that people appreciate it so much, that was the thing that drew me to it.” Alongside a recent brand refresh, Karel’s first big project is a new bar and shop between an old decommissioned red metal brew kettle and their coolship. He’s confident he and Jos are ready to take on their father’s legacy. “I think we're going to write our own chapter in the book of Boon,” Karel says. “There's definitely pressure...but I think we're capable.”

*

Leaving Boon behind, the Zenne skirts a clump of industrial units and hibernating fairground attractions. It’s hemmed in by scraggy mudbanks, made slippy by recent storms, directed first towards the nearby Brussels-Charleroi canal and then into a quiet wooded demesne on the other side of Lembeek. Rising in brackish fields outside the Wallonian village of Soignies, the Zenne trundles 103 kilometres through flat Brabantian fields and under Brussels’ streets before eventually dumping its brown waters in the larger Scheldt river near Mechelen.

It’s easy to underestimate the importance of this furtive tributary to the surrounding valley, cowed as it is now by the canal, the railway and the motorway that crowd its banks and overwhelm the songbirds with their incessant thrum. But the Zenne once drew neolithic tribes, Roman legions, and Burgundian dukes to its banks, an important economic motor and umbilical cord connecting the region to the wider Low Countries. For many centuries, it was thought there was something magical in the valley’s air, a benevolent miasma created by the Zenne that enabled the brewers who settled its banks to brew Lambic and its spontaneously-fermented precursors.

Halle is the next town downstream. The river settles into a winding thread parallel to but separated from the canal as it disappears behind clanking red brick factories and quiet industrial buildings with copper roofs and cracked windowpanes, before re-emerging behind a derelict sugar refinery on Halle’s fringe.

It was a Halle tax collector, some say, who first committed a Lambic recipe to paper. In 1559 Remy le Mercier, an employee of the city, described in his papers a beer made with wheat and barley in quantities roughly analogous to those later employed by Lambic brewers. Subsequent researchers are less sure, pointing out that it was not Lambic Le Mercier’s text described but to Keute and Hoppe, two distinct local beer styles made in Halle, Brussels and nearby settlements..

And while it’s true that the first explicit written reference to Lambic occurred in Brussels in 1794, maybe this is nitpicking. Lambic, Keute, Tarwebier - whatever they called it, people have been brewing spontaneously-fermented wheat beer on the banks of the Zenne for centuries. Halle even had its own local beer style - Duivels Bier, ‘devil’s beer’ - which flourished in the 19th century. But it was Lambic, and later Geuze, that proved the most capable of winning the hearts and throats of Zenne valley drinkers. So much so that in 1955 poet Hubert Van Herreweghen wrote that a Brabander “could taste life itself in a glass of Geuze.”

But there’s little evidence of this rich brewing heritage in modern-day Halle, and the river too struggles to make its presence felt. It runs alongside a park littered with the chipped memorials to dead Belgian colonialists before vanishing from street level underneath a tangle of inner-city streets, the former path it once cut through the town marked occasionally by a faint blue line in marble on cobbled laneways. It emerges on the other side of Halle into car parks and crumbling reinforced concrete culverts in the shadow of looming steel grain silos, before dipping underneath the canal and returning above-ground into a quieter stretch of wooded riverbank. From there, a slippery walking track made more of an obstacle course than a walking route by the recent rain follows the Zenne through more semi-industrial landscape to the Buizingen train station before the path and river take separate and uneventful routes to the suburb of Lot.

*

Lot

In his famous essay on Geuze, Van Herreweghen challenged the maxim that the soul of Lambic - and of the Zenne valley - resided in the magical properties of its air: “Geuze is a product of the soil and the soul of Brabant…a beer gifted to us by the earth.” The poet would have had a lot to talk about with Werner Van Obberghem, because Van Obberghem likes to talk about soil. “When talking about lambic, people always talk about our terroir as being the air, but the real terroir here is in the soil,” says the business manager of Brouwerij 3 Fonteinen. More specifically, he likes to talk about what grows in the soil of the Zenne valley and how important it has been to Lambic brewing traditions.

It’s the soil - loamy soil - that has made the Zenne valley basin a good place for farmers to grow wheat and barley for centuries. The Zenne valley and the Pajottenland are more or less synonymous geographical descriptors for the area of rolling hills on either side of the river to the south-west of Brussels, though the catchment area of the latter stretches northwards, loosely agglomerating the semi-pastoral landscape between Halle and the city of Ninove on the river Dender.

Whatever it’s called, it’s Brueghel country, and rivers, wheat fields, and beer feature prominently in the painter’s work beside misshapen Flemish peasants. And in the tap room of the brewery’s “Lambik-O-droom” in Lot, separated from the river by a ribbon development of pitched-roof post-WWII rowhouses, Werner explains the particular merits of Zenne valley wheat. “I'm not the best historian,” he says, “but the Payottenland has historically always been the breadbasket of Brussels.” Several years after taking over 3 Fonteinen from its founder Armand Debelder, Werner together with his colleague Michaël Blancquaert, has determined to revive the valley’s moribund wheat- and barley-growing traditions. Moribund may not be quite the word, because farms in the Payottenland continue to grow wheat and barley for industrial use (and some baking), and corn for cattle-feed, but the link between the region’s agronomic terroir and its brewing traditions has been severed.

3 Fonteinen’s own roots lie further downstream in the village of Beersel, where in the 1950s Debelder’s father Gaston opened a café-restaurant of the same name and began - like many cafés in the region - to blend his own Geuze. When Gaston retired in 1982, Armand took over the blending before installing a brewery behind the café in 1998. In September 2016 the Lambik-O-droom opened as a tap room for visitors and as a home to the brewery’s barrels. In the summer of the following year, sitting and chatting in the tap room, Werner asked Armand where they could take the business next. Armand, across the table from him, banged his fist. “Let’s go further!” he said. “We need to get our cereals from our back garden again.” And so began 3 Fonteinen’s efforts to reconnect the brewery, and the region’s farming community, with a terroir that existed not in the air or in the wood, but deep in the ground.

3 Fonteinen’s usual suppliers were unable to tell them exactly where each batch of their wheat and barley came from, so Werner went looking for someone who could do that and guarantee a local supply. 3 Fonteinen had already done something similar with local cherries, helping to rescue the local Schaarbeekse Kriek variety once used in the region’s Kriek beers but which was almost trampled into oblivion by the valley’s rapid urbanisation in the 20th century.

The Granennetwerk would turn out to be a little more complicated. After several years working with a couple of local organic and community-supported farms, several pilot projects, and an investment worth around €400,000, Werner and his team have propagated 30 old barley varieties and +35 original wheat varieties - grains like the Kleine Rosse van Brabant (“the little redhead of Brabant''). They are now brewing with Zenne valley-grown heritage grains, with some of it already ageing in the Lambik-O-Droom’s 8,000 hectolitre-capacity barrel store.

Brewing with local heritage grains has thrown up unexpected results, every batch of these new-old grains subtly different and unpredictable in a way their more modified contemporary equivalents are not. “It's a challenge,” he says, “[But] it’s causing us to come back to what Lambic blending actually is, which is really using a lot of different flavours or aromas and tastes and try to make an excellent Geuze every time.” Presumably it has also been a welcome distraction during the pandemic. Like their colleagues in Lembeek, 2020 brought with it business and financial complications, ones which were not helped by the fallout from the collapse of their American distributor.

Werner also believes the Granenproject taps into a shift in consumer mood, one in part driven by the pandemic. “We do see a change...especially with those aficionados not only from the beer world, but also the natural wine world,” he says. “People are becoming more critical about what they're consuming. That's where we want to be part of and it's a responsibility that we want to take up - not only for 3 Fonteinen but also to ensure there is a decent economy for everyone who works in beer.”

The pandemic also jolted the business to rethink its sales routes, launching a webshop, negotiating with distributors and shipping companies. Werner’s eye is firmly on keeping the business going, protecting Armand Debelder legacy at 3 Fonteinen and, like the Boon brothers, conscious of how he can contribute his own. “If this is our life's work…[and] if we can continue what we are doing until our pension then we are the happiest people in the world,” he says. “That's the truth. [But first] we still have a lot of things to do.”

*

Beersel

Part of the same municipal district, and tethered together by the river, Lot and Beersel are inextricably linked by 3 Fonteinen’s history, the Debelder family tree, and the Lambic revival of the past 30 years. Leaving behind the Lambik-O-Droom the Zenne turns into Lot village, where on a rusting humpback bridge the local burghers have erected a small monument to the Zenne and to the brewers it has inspired. Beyond the bridge the road and river diverge, the Beerselsestraat launching into a steep climb from the valley floor towards Beersel while the river continues its meanders through vacant mossy fields.

The road loops up and around the Kasteel van Beersel with its squat tricorned keep and fairytale pointed turrets before reaching the top of the Beerselberg hill and a small square dominated by the 20th century nave and 15th century belltower of the Sint Lambertus parish church. The square is named after writer Herman Teirlinck, born in Brussels in 1879 but who made Beersel his home from 1933 until his death in 1967.

From an upstairs window of his nearby villa, Teirlinck could trace the Zenne’s lugubrious passage towards Brussels, could watch as the river burst its banks, as poplars grew high in the fertile fields on either side, could spy on the ducks, geese, and the swans making their homes in it, and in all of this could feel the spirit of Bruegel and of Brabandiers past in his “little piece of untouched valley, a sliver of the virginal river Zenne''. The river was for him a “a vivid witness of bygone ages, a place where ancestral blood still pulses and trembles''.

When he wasn’t at home, Teirlinck was often found in the cafés around the Beerselberg. He’d sit by the bar, a glass of geuze or kriek in front of him, and fall into conversation with the barman. One evening in the early 1950s, Teirlinck found himself listening to the cafébaas of De Drie Fonteinen complaining of gastro-intestinal issues. Gaston Debelder’s guts hadn’t been right since the end of the war. Captured in Belgium by the Nazi occupiers, Debelder spent time in prisoner-of-war camps and working as forced agricultural labour. Afterwards, he was plagued by stomach troubles caused by the ill treatment and poor diet he’d suffered as a prisoner which made it hard for him to digest anything. Neither local doctors nor specialists in Halle were able to offer him anything other than solace.

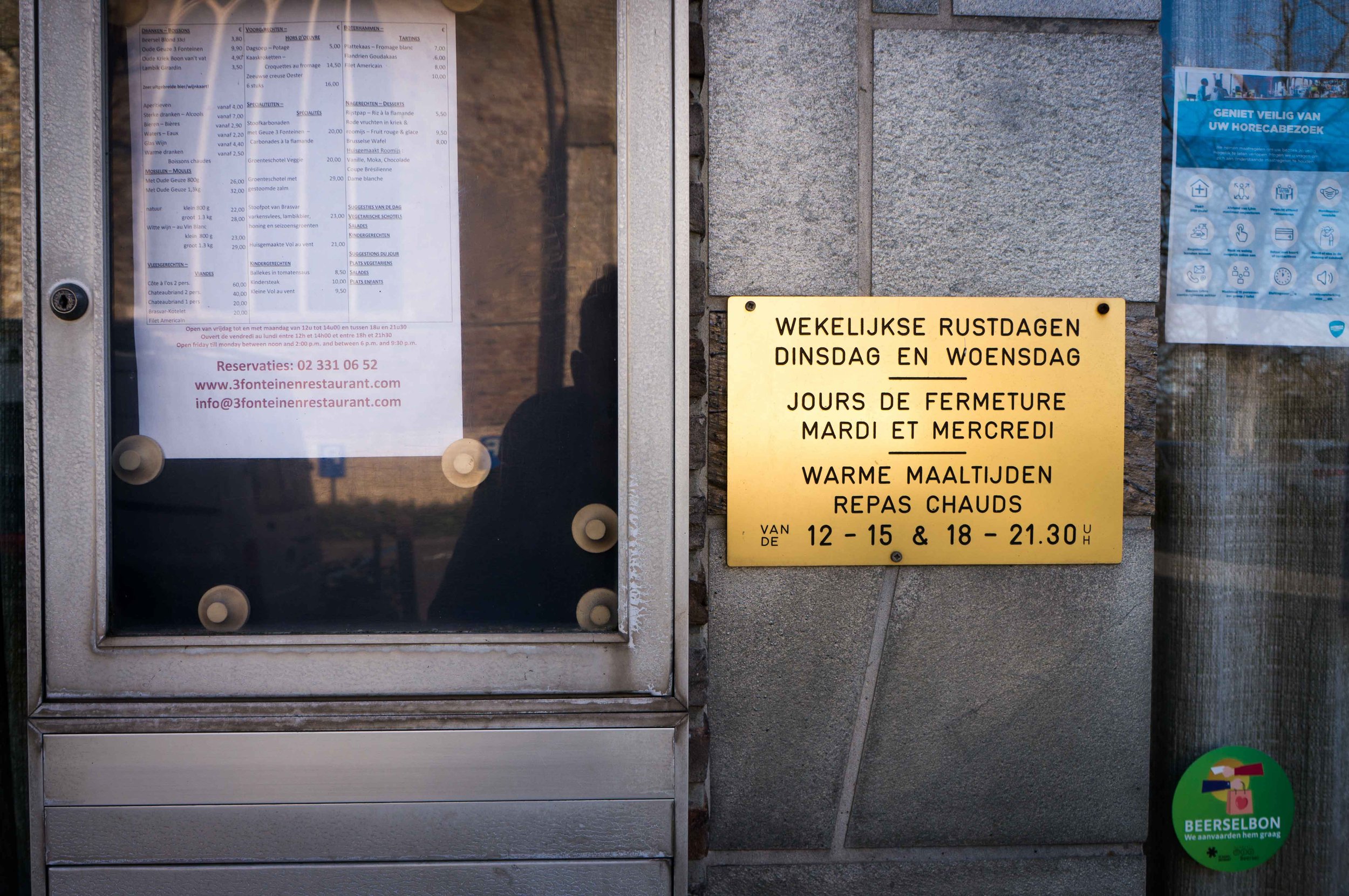

Teirlinck listened to Debelder’s story and gave him the name of a doctor friend who he thought might be able to help with Gaston’s abdominal ill-fortune. The doctor’s advice was simple: drink some Geuze and it will set your intestines right. Debelder took the advice one step further and began blending his own Geuze for the café. In 1962, when Gaston and his wife Raymonde bought a site opposite the church, they knocked down the existing building, rebuilt it as a the new café-restaurant De 3 Fonteinen, and continued the blending he had started several years previously.

“I have to admit that those things really defined my grandfather. For a very long time,” says Thomas Debelder, Gaston’s grandson and successor at 3 Fonteinen. He’s sitting in the café-restaurant empty sunlit terrace having just uncorked a cob-webbed bottle of Drie Fonteinen Kriek. The beer has become jammy and vinous and earthy in the 25 years since it was bottled in the brewery next door and moved 100 metres to the cellar underneath the restaurant.

The Debelder family are no longer involved with the brewery built by Thomas’ uncle Armand, but they continue to run Gaston’s restaurant. Thomas rarely spoke to his grandfather about his wartime trauma but its physical and mental consequences cast a long shadow on the Debelder family. Gaston was already 43 when Thomas’ father, Guido, was born and Thomas remembers being the only child at school with a WWII-veteran for a grandparent. “He always told us to be happy with what we have. And then he told us why, but that he never wanted to go into details,” Thomas says. He didn’t want to push him, knowing how emotional the subject matter made his grandfather and knowing too how hard those immediate post-war years were for the family. “There's a lot being written about Belgium during the Second World War,” he says. “But the years afterwards were even harder.”

The Debelders survived them and in the 1960s and 1970s the 3 Fonteinen - named after the three hand pumps that were used to serve beer - flourished. Teirlinck was a regular, the restaurant hosting his weekly “Mijol” literary club, and Gaston began bottling the Geuze he was blending for his customers. When Gaston retired in 1982 Guido took over the running of the restaurant with Thomas’ mother. On the face of it, little seems to have changed since then. A portrait of Teirlinck still hangs above dusty shelves of beer across from the bar, and the only difference diners might notice is the greater likelihood of hearing foreign accents at the next table - 3 Fonteinen having become a permanent fixture on the pilgrimage trail of American, Italian, and Japanese Lambic drinkers in the intervening 30 years.

But the dusty shelves and the empty lunchtime terrace betray the unexpected change that arrived at the restaurant’s door on the evening of March 13, 2020. The previous day, the Belgian authorities had registered 399 cases of COVID-19, 20 of which were in intensive care, and three deaths. Then-prime minister Sophie Wilmés announced that as of midnight on Friday the 13th, bars and restaurants would be closed until early April. “It was so crowded,” Thomas says of the dining room that Friday evening but with midnight approaching, Thomas and Guido stopped serving and started encouraging customers to head home. Then, at five past midnight, the police arrived. “And I was like, ‘Okay, no problem...everyone has to leave right now’,” Thomas says. Diners, not wanting to abandon the last of their beers, asked if they could take their glasses outside and leave the empties in front of the restaurant when they were done. Thomas took some grief from the police, but told them he would clean up in the morning. “And then I went to bed.”

They didn’t re-open for indoor dining until June, and then only for a brief period before a second national lockdown followed in early October 2020 that lasted through to the following spring. The abrupt closure of the café was a shock for Thomas, his father Guido, and the rest of the family. They are all tied to the rhythms and routines of the restaurant business. They had lived upstairs - Thomas on the first floor, and Armand’s family on the second - since the 1980s. Armand’s wife had worked in the kitchen, and Thomas’ too.

Even after his retirement in 1982, Gaston would come down from Halle where he lived to chat with regulars in the dining room. Guido has the same itch. “He really needs to see people,” Thomas says. “He needs, on a Sunday, to be in a restaurant and to say hello to everyone.” And when the pandemic prevented this, Guido took to riding around the surrounding countryside delivering meals to friends and valued customers. This eventually grew into a more structured Sunday traiteur service, Thomas’ mother on the phone taking orders, and Thomas in the kitchen. It was a weak imitation of the usual weekend crush but it helped the family through the rough months of lockdown.

Thomas, like his father and grandfather, has also caught the restaurateur bug, and he’s particularly missed the foreign visitors who would arrive in high spirits at the restaurant for dinner after a day’s gallivanting around the valley’s breweries. “At the beginning of the 90s we didn't have any Americans coming for Lambic to Belgium,” Thomas says. “And then Michael Jackson came along and things [really] started.” The restaurant has become an important local part of this Lambic revival, and towards the end of 2018 Thomas considered following in Gaston’s footsteps by blending his own Geuze for the restaurant on-site.

But that project, and others, fell victim to a succession of personal, professional, and familial complications in 2019. Then came March 2020 and all thoughts of experimentation have dissolved into a clear-eyed focus on keeping the business afloat until some kind of normality resumes. “I'm not getting any money. I'm just….surviving,” Thomas says. “And that's the thing. I want to do other things than just balancing the books every month.” The pandemic’s mood of uncertainty has also worn down some of his instinctive adventurism. “I have more time [but]...I’m hesitant to try new things,” he says. “You never know where we will be in two years.”

Some of that free time has been spent with his house-bound kids, helping them with homework and baking with them. He’s been walking the hills around Beersel, seeking out quiet fields away from the chaos of a full house. And he’s been thinking about Gaston’s experience and sacrifices. “He lost a lot of years of his life,” Thomas says. “And we now...we think we lost a year. But in fact it wasn't that bad. We didn't lose our lives. We didn't lose any friends…all of [Gaston’s generation], they lost friends, children, and family in the war.”

Our Krieks finished, Thomas walks me across the square, around the church and down a sloping muddy path and we part ways on a bridge on the river - him to return to the restaurant, and me to follow a dirt track heading for Brussels. The Zenne curves itself away from this Broekweg - “stream path” - and disappears behind a string of leafless trees. On the other side of the path a green chain link fence separates me from the roar of the eight-lane E19 motorway. Further on there’s a gap in the fence leading to a petrol station and a nondescript trucker’s hotel which was, several weeks previously, the site of the grizzly murder of a hotel worker by a French man on the run from a psychiatric facility.

Blackbirds hidden in the bushes try to make themselves heard above the traffic as the river dips in and out of view, swerving industrial units and thorny bushes littered with white bin bags, empty cans and rotting leaves. The thudding of nearby cars gets progressively louder until the Broekweg stops by electricity pylons and spits me out into a dusty, empty side road between the motorway and the river - sloppy mud banks now replaced by chipped concrete culverts. An exhaust-stained yellow warning sign exclaims “Drogenbos”.

In the 1950s, Herman Teirlinck worried what the encroaching post-WWII, car-centric modernity that was engulfing Belgium would do to his beloved “Brabantian Breughel reserve”. Drogenbos is Teirlinck’s 20th century nightmare made mundane 21st century reality. It is almost-but-not-quite Brussels, which is just out of reach beyond the horizon. The river and my dirt track emerge together into a cacophonous exurban mess of German car showrooms, French supermarkets, Belgian burger chains and American pizza huts.

The air is thick with dust kicked up from the 10-lane highway that separates Flanders from Brussels, and the Zenne has wisely disappeared into a swampy morass, abandoning poetic inspiration in favour of base survival. But not far from this semi-industrial, semi-suburban wasteland, across the highway, under the railway and over the canal, there is a place that still beats to the old rhythms of the Zenne valley.

*

Ruisbroek/Sint-Pieters-Leeuw

“Lambic was a drink for the ordinary people,” says Jo Panneels, co-owner of the Lambiek Fabriek brewery. “It was nothing special.” Jo, like the Boons and the Debelders, grew up in the Zenne valley. His grandmother was the cafébazin of the Gildenhuis in the village of Dworp, where she doled out Geuze and Kriek from local breweries Winderickx and Dekoninck to her neighbours. Jo’s grandfather would teach him how to carry a bottle up from the bar’s cellar, how to hold it just right so that he didn’t disturb the sediment on the bottom and serve a customer a cloudy beer. Learning about Lambic at his grandparents’ knee, it never struck Jo as particularly exceptional. And the state Lambic was in then, he probably never imagined he would end up running a Lambic brewery - one that is playing a pivotal role in the next phase of Lambic’s evolution.

Jo meets me at the brewery’s entrance and ushers me through a glass door and into the ersatz bruine café that serves as the brewery tap room. Lambiek Fabriek’s story started in a bar like this, with a 23-year-old Jo and his friends drinking and complaining about what they were drinking. “We can do this also. But better,” Jo said to the group. It was only meant, he says now, as youthful grootspraak - boasting - but before long they were experimenting with blending their own Lambic in glass carboys in someone’s garage.

Then came encouraging words from Frank Boon, followed by slightly less encouraging words from some of the other Lambic brewers. Pretty soon they had invested in a couple of barrels stored in a warehouse in the nearby village of Ruisbroek. But as their ambitions grew, Jo and co. had a problem. Two, in fact. The other Lambic brewers - who provided the base wort for their Lambic experiments - didn’t, or couldn’t spare any of their output. Meaning they were faced with a choice. They could continue as amateur blenders and survive on scraps from the existing brewers. Or they could start brewing their own beer and loosen their reliance on the good graces of others. Option two meant they would become the first new Lambic brewers in the valley since Armand Debelder started brewing out the back of the 3 Fonteinen in Beersel in 1998. It also meant being creative, because Jo and his four friends couldn’t afford to buy a brewhouse - new or second hand. Enter the Belgoo brewery.

Belgoo, a short walk from the canal through a dull neighbourhood of gyms, paint stores and suburban bungalows, is a conventional brewery founded in 2007 that makes Blondes, Saisons, and Belgian IPAs. In 2016 when Jo and his friends came calling, instead of vacating the premises Belgoo and the newly-christened Lambiek Fabriek decided to share it. They use the same brewing vessels to make their wort, but otherwise everything is separated. Separate bottling line. Separate fermentation tanks. Separate blending vessels. That way, the assertive bugs living in Lambiek Fabriek’s barrels don’t infiltrate and overwhelm the more orthodox microorganisms employed for fermentation by Belgoo, and everyone’s happy.

It’s a set-up that might bring contemporary brewers out in hives but this is a cohabitation not without precedent in the Zenne valley. In the early 1920s, as Brussels’ industrial breweries shifted from making Lambic to foreign beer styles, breweries like Atlas in Anderlecht similarly produced Lambic and Faro alongside German-inspired Lager beers. However it came about, it’s been a successful partnership, with one of Belgoo’s founders joining Lambiek Fabriek’s ownership team. It is, however, a tight fit.

Lambiek Fabriek’s footprint is most obvious in the large storeroom filled floor to ceiling with around 250 stacked barrels - mostly repurposed red wine barrels but some previously used for fortified wine - and a collection of large Italian foeders. But the real giveaway that Lambic is brewed here is kept in an adjoining lean-to. Lambiek Fabriek’s coolship, a hallowed piece of Lambic brewing equipment and where the magic of inoculation by wild microflora begins, is hoisted four or five metres off the ground by metal pillars. Accessible only by ladder, it rests on a large platform just under a pitched roof, surrounded by wire mesh to keep out inquisitive pigeons, the space below it strewn with discarded tools, an old motorbike, and rusting brewery paraphernalia.

As Panneels explains while he gets a ladder, having the coolship there not only maximises the little amount of space they have, it also helps optimise the circulation of cold air when there’s beer cooling in it overnight. “It’s [all] old-fashioned, but it works,” Jo says. Thomas Debelder, back at 3 Fonteinen, called it the “stupidest idea he had ever heard” (Thomas remains a loyal client and advocate of the brewery’s beers). As of my visit in early January - lambic brewing season stretching from October to March or April - the coolship has already chilled around 40 batches of fresh wort.

Alongside traditional Lambic and blended Oud Geuze, Jo and his colleagues at Lambiek Fabriek have not been afraid to step away from Lambic orthodoxy to try something different. Fruit Lambics beyond the traditional Kriek, for example, including grape and blueberry blends. A whiskey barrel-aged Lambic aged with barrels from Het Anker brewery in Mechelen. And Bord-Elle, a panic-inducing, big-bodied 12% ABV beast of a beer. To keep up with their growing output, Lambiek Fabriek kept their original Ruisbroek warehouse and expanded into a new barrel warehouse in Lot, on the other side of the Zenne from the Lambik-O-Droom.

Lambiek Fabriek is a young business in Lambic brewing terms, one that so far has been able to balance fealty to the culture’s traditions with an exploration of the outer limits of that orthodoxy. The mere fact of Lambiek Fabriek’s existence is proof to other young tyros with Lambic ambitions that new entrants can enter this old world and find success. In the years since Lambiek Fabriek started brewing in 2016 a host of new breweries and blenderies have opened. “It’s in the blood,” around here, Jo says. And despite the impact of the pandemic on him and the valley’s other brewers, Jo doesn’t think it will be life-threatening. “I don’t have worries for Lambic anymore,” he says.

Jo waves me off from the brewery’s cluttered yard and I take the road back to Drogenbos to pick up the Zenne’s thread before it reaches the Flanders-Brussels border. My north star is a concave power station cooling tower that looms over the factories and warehouses between me and the river. Following the river’s trail as it runs parallel to the Boulevard de l‘Humanité, it feels like I’m in a decompression chamber between the valley behind me, and the disordered city ahead of me, with only deserted brownfield sites, Ibis budget hotels, paint wholesalers, passing cars and the irregular whoosh of nearby trains for company.

*

From Lembeek to Drogenbos the river has just about maintained its place in the landscape even as it has been crowded out by the canal, the railway line, and the motorway. Apart from the occasional flood, the Zenne west of Brussels lives a mostly sedate existence. For the valley’s Lambic breweries, the pandemic has been disruptive. But there are barrels in Lembeek that have lived through multiple pandemics, some of them containing beer brewed before anyone here had ever heard of SARS-CoV-2. Had it arrived in the Zenne valley three decades earlier the virus’ impact could have been terminal. Lambic brewing is in relatively ruder health these days and, as Thomas Debelder says, they’ve been through worse.

The same could be said for the Zenne that emerges into Brussels from out of the bowels of the power station. Herman Teirlinck once wrote that Brussels was so ashamed of the “disgusting” Zenne, which once brought prosperity and trade but by the 19th century had degenerated into a corpse-bloated sewer bring plague and disease within the city’s walls, that it “locked it up underground and buried it in stone.” And while it is not the same bucolic stream as the one that winds past Boon and Beersel, the Zenne’s prospects in Brussels have never looked better.

There is hope that, where the river was once a murderous nuisance, in the coming decade it will play a crucial role in helping Brussels deal with the consequences of this pandemic and with the challenges faced by the city in the coming climate emergency. For the city’s brewers, whose predecessors built brewing empires on the back of the river, the picture is less rosy. Theirs is a young industry with roots much less deep than their Lambic colleagues. And unlike their friends in Lembeek and Lot, brewers in Brussels think in terms of weeks and months, not years. Looking at it in early 2021, with no end to lockdown in sight, this pandemic could be just as catastrophic to the city’s hospitality community as anything experienced by their predecessors 150 years ago.

But that’s a story for another time.