On the lash with Baudelaire // A literary pub crawl through Brussels, Act One

Brussels throughout its history has been home to many writers and artists, from Victor Hugo to the Brontë sisters, through to James Joyce and Hugo Claus. Some of them have been temporary visitors, others permanent, and many reluctant. Nobody exemplified this genre of Brussels resident better than Frenchman and serial flâneur Charles Baudelaire. Prompted by a recently-organised exhibition about Baudelaire’s ill-fated time in Brussels, I set off on a tour, in his and others footsteps, of what remains of Brussels’ literary haunts (Part two is here.)

"Faro, synonym for urine!"

Charles Baudelaire hated Brussels. From his arrival in the city in 1862, indebted and unloved, until he left two years later a paralysed syphilitic, he did not mince his words about Brussels: “a ghost town, a mummy of a town, it smells of death, the Middle Ages, and tombs”. Its people: “An amazing quantity of hunchbacks”. Or its women: “Monstrous bosoms typically developing quite precociously, swelling like swamps owing to the humidity of the climate and the gluttony of the women”. Worst of all, he despised the beer drunk in Brussels, cursing faro as a “synonym for urine!”.

It seems logical, then, to start a pub crawl that is loosely in his honour, at a chapel geuze, faro, and kriek – beers he loathed so viscerally. The beer on tap at À la Mort Subite (Rue Montagne aux Herbes Potagères 7) might not be made in Brussels anymore, and it may be a poor imitation of the real thing, but it still flows here, and the place has long been popular with the arty set. Maurice Bejart, the French-born dancer, choreographer, and opera director would come here while working at the Theatre de la Monnaie nearby: “From the start, there was one place that tempted me…an old café full of old mouldings and faded mirrors whose name exploded in pseudo-erotic-gothic red neon”.

“Faro, synonym for urine!”

The sign, the mouldings and the faded, chipped mirrors are still here, and I don’t suppose the level of service has changed much, either. Uncompromising waiters in black smocks and white shirts navigate a mix of locals and tourists packed in around old wooden tables. One bustles over to my table, and offers the merest acknowledgement of my order of a glass of faro and an omelette with a disinterested “only cheese?” in response. Despite this brusqueness, like Bejart, the Morte Subite remains one of my favourite places to drink in Brussels.

"An old café full of old mouldings and faded mirrors"

My faro arrives in a thick-cut class, muddy brown and sweet, lacking much sour pucker. It is followed soon after by my omelette. Baudelaire would have hated it. He scoffed at the “Belgian” omelette as “flat, not bound, barely beaten, without seasoning, and therefore bland and indigestible.” Mine is just fine, and what sourness there is in the faro cuts through the fatty, cheesy, egg.

The bar soon breathes a little easier as a large group of Italians with sharp accents and rolled cigarettes pack up their gear and leave. I follow them out the door shortly after, stomach set for a day of boozy flâneuring.

I take the sloping Rue de L’Ecuyer down to Place de la Monnaie. The square is bound on one side by the Theatre de la Monnaie – home to the Belgian opera – and the Flemish Muntpunt library, and on the other by a brutalist monolith housing the Brussels City administration. This part of Brussels drips with literary connections. It was here that Belgian revolution began in 1830, sparked when the local bourgeois took against an opera performance. It was also here that Brussels’ first Parisian-style café was opened and where many of its earliest literary cafés were located. None of these establishments remain, but the Muntpunt library houses a café (Rue Léopold 2) on its ground floor. That is where I head, wedging myself at a table between the window and a crochet and knitting club.

“What leaves me quite cold are the mass of German girls, all manufactured from a single model one would say, that one sees at the café concerts. It seems that one sees that same breed everywhere nowadays, like Bavarian beer.”

“Depot de la Brasserie Löwenbräu a Munich”

Service is slow, so I rouse myself to the bar. The drinks menu is, oddly for Brussels, dominated by West Flanders’ Omer Vander Ghinste Brewery. I order their Export Blauw, a lager beer resurrected from the brewery’s 1950s back catalogue. Lager beers have long had a hold over Brussels and this square in particular; the Café les Trois Suisses, which once stood on the other side of the theatre, was decorated with a sign the length of the café proclaiming it the “Depot de la Brasserie Löwenbräu a Munich”.

John Dos Passos, the modernist American writer, wrote about passing his childhood here with his mother, “solemnly sipping my milk and eating my madeleine, while gnomes and old men with beer mugs leered at me from the walls, from behind placid ladies and gentlemen taking their déjeuner.” The centrepiece of the café was a golden lion that would roar and flash its eyes red whenever a new barrel of beer was tapped. It is all long-demolished.

Löwenbräu and their German fellow travellers did not find favour with many of the city’s artists and writers, Vincent van Gogh among them. In a letter to his brother Theo sent during his time living in Brussels, he complained that, “what leaves me quite cold are the mass of German girls, all manufactured from a single model one would say, that one sees at the café concerts. It seems that one sees that same breed everywhere nowadays, like Bavarian beer. It seems to be an article that’s exported in bulk.”

Stick to the painting, Vincent. This Export Blauw is a deep straw colour, with a head that dissipates quickly. It has a grainy-sweet aroma, with a green, vegetal hint. It is malty, bready with a little bitter twinge in the finish. It is perfectly serviceable, and doesn’t get in the way of people watching. The Grand Café Muntpunt is a busy place, catering to the student overflow from the library, families hunched over the soup of the day, as well as the crocheters.

“The windows of the breweries opened. The tables filled with their glasses of lambic and faro. A blue haze enveloped the rooms. ”

"Cold streets tangled like old string"

I leave them to their stitching, and shuffle into W.H. Auden's “cold streets tangled like old string” of inner city Brussels. My intended destination is down the Rue des Fripiers and left onto the Rue du Marché aux Herbes. L’Imaige Nostre-Dame (Rue du Marché aux Herbes 8) is one of a pair with Au Bon Vieux Temps, both hidden behind parallel arched alleyways. L’Imaige was the successor to the likes of Les Trois Suisses, opened by a failed Dadaist gallery owner and catering in the 1930s to the city’s surrealist artists and writers. It is still standing, albeit reduced to serving taster flights of Belgian beers to tourists for €12. When I pass down the Impasse des Cadeuax and through the entrance, there’s a couple of old soaks at the bar and the rest of the tables are full. No reason to linger.

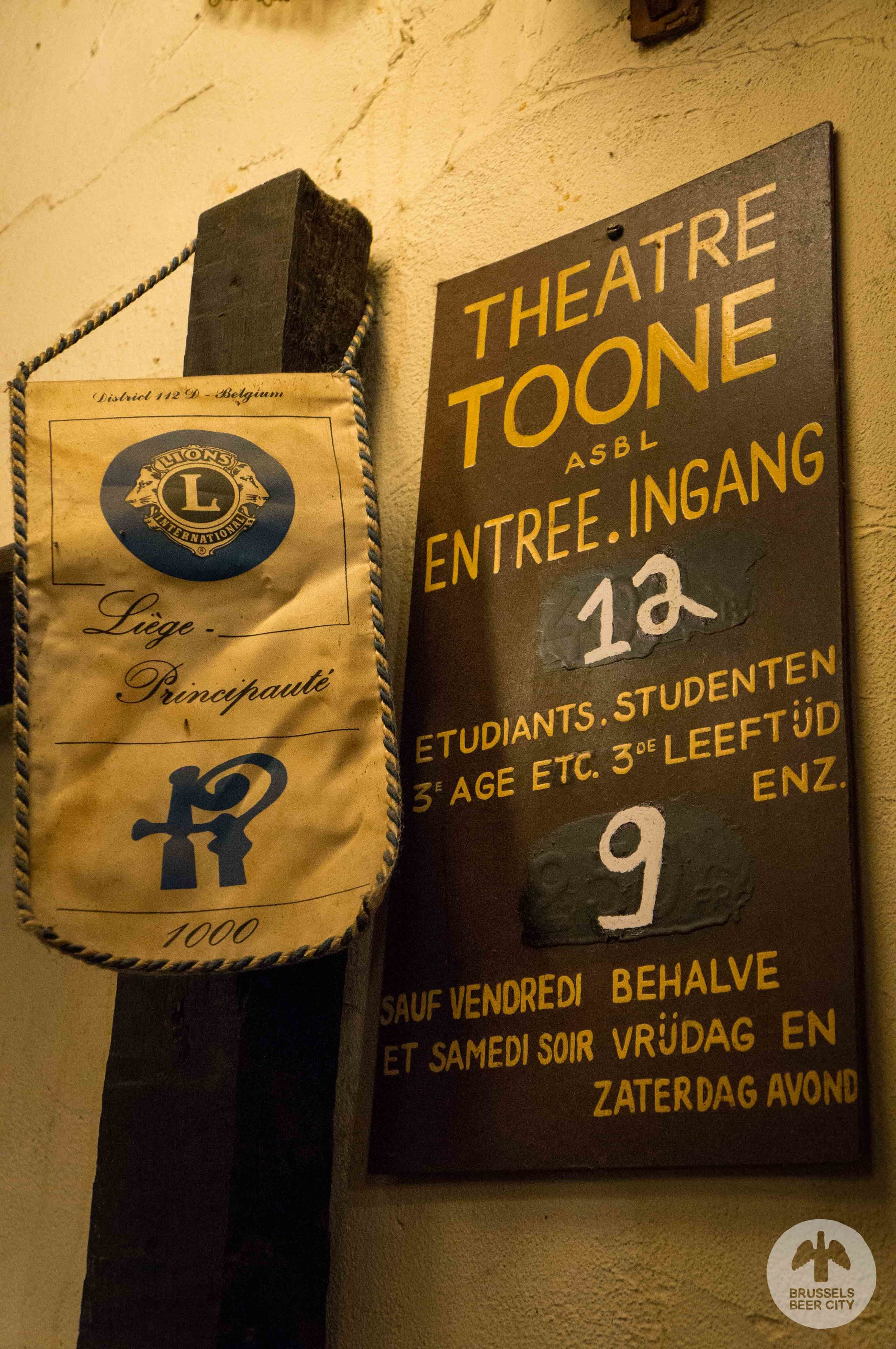

A surer bet is a little further up the street, also in its own darkened alleyway. As luck would have it the Théâtre Royal de Toone (Rue du Marché aux Herbes 66) is both open and empty, save for a knot of students at a table near the entrance. In the main room, faded wooden bleachers have been folded away to make room for a jumble of tables and chairs. Facing the bleachers is a puppet stage hidden behind chicken wire.

“Brussels - A ghost town, a mummy of a town, it smells of death, the Middle Ages, and tombs”

I sit down at the table nearest the stage. It feels like the puppets could spring on stage at any moment, and the bleachers unfold themselves out on top of me. Fortunately, the theatre programme tells me that the real stage is up in the attic. A mumbled order and a sheepish young waiter lands me with a Boon Kriek, which isn’t his fault, I suppose.

The Toone is a puppet theatre that moonlights as a brown café, a proper Brussels estaminet, a warren of rooms succeeding one another through to the back of the building. Writer Camille Lemonnier described 19th century estaminets of Brussels as:

“…houses where one consume especially beer. (...) Here, a rudimentary simplicity reigns: on the walls, yellow and blue notary sales posters for any ornament, sometimes cages with canaries, an enameled dial like a big eye, or an old carved clock. Obviously, any distraction that could disturb the customer in the tasting of the fermented liquid is discarded as detrimental to the gravity of this occupation.”

"Too many people with wooden souls not to save little wooden people with souls"

That rudimentary simplicity has made allowances for some decoration in 2018. Wooden puppets and their wooden heads, together with royal portraits, now hang from the walls. It is the royal theatre, after all.

The theatre is run by the 8th in a line of “Toones” (a bastardisation of the name Antoine) stretching back to the 1830s. The Toones have been running puppet shows at this spot since 1966, but their spiritual home were the impasses and dead end streets of the Marollen. There, they bounced around under different Toones (a non-hereditary position) and at different venues until crises in the 1960s threatened the theatre with extinction. French director Jean Cocteau lent his support to the efforts to save the theatre, advocating for its rescue because “there are too many people with wooden souls not to save little wooden people with souls.” It survived, eventually even thrived, and the current Toone continues to run plays about Brussels folk stories, Belgian history, and literary classics like Dumas’ Three Musketeers. All in near-impenetrable Brussels patois.

A cat creeps under my table, startling me out of my reverie and spurring me on to finish my glass of sweetened cherry juice and drive on to my next stop, just around the corner.

Victor Hugo called Brussels’ Grand Place a “miracle”, the city hall building “a dazzling fantasy dreamed up by a poet, and realised by an architect.” He had enough time to form a considered opinion; when not visiting sex workers in the neighbourhood around the Place de Barricades, he twice called the square home. He was, like his contemporary Baudelaire, an exile from France. His problem was not debt but unkind words written about recently-installed French emperor Louis Napoleon that had forced him to flee from Paris to Brussels in 1851.

Writing the Communist Manifesto in a Brussels backroom bar

La Chaloupe d’Or (Grand Place 24-25 - NOTE: it is currently closed due to bankruptcy) is next door to one of his lodgings, and a window seat on the first floor gives a view out over the square, across to the Maison de Brasseurs and the Maison du Cygne. It was in a backroom of the Cygne that Karl Marx knocked together the Communist Manifesto in between stays in prison and rabble rousing among the city’s German workers. Marx’s thoughts on geuze are unknown, and Hugo was apparently fond of a faro, but I follow the tastes of another of the city’s Gallic literary exiles and order a witbier.

Charles-Marie-Georges Huysmans, writing as Joris Karl (JK) Huysmans, is most famous for the novel À Rebours, which features a louche, dilettante central character in possession of a gemstone-encrusted tortoise. Before he hit the literary big-time he moved to the Brussels in 1876, and to escape "the expanse of a dull gray” sky he drank all that Brussels' bars could offer: “faro, lambic, “blonde, brown, and “those of Leuven, sweet and cloudy”. This Leuven beer was likely a “Peeterman”, a now-extinct known for its sourness and part of the wider family of wheat beers of which Hoegaarden and its variants are the only remaining examples. My witbier arrives, but it lacks this refreshing tartness and is instead a bog standard blanche, soapy and citrusy.

"Delirious drunkenness"

Huysman visited the Grand Place one Sunday morning just as it was opening up:

“…the windows of the breweries opened. The tables filled with their glasses of lambic and faro. A blue haze enveloped the rooms. Skulls of bald billows, disordered snouts, pives, hunchbacks of lint warts, and vitelottes, scarlet-coloured in the coppice of moustaches, tramps of drunks on a spree, and caboshes of delirious drunkenness, were fading away. A burlesque mess in the swirling smoke…The groups were getting bigger, they were calling out the window, they were shouting the Brabançonne at the top of their lungs, they were stuffing themselves with Dinant's cakes, they were stuffing themselves with buttered pistolets, they were pounding rusks, they supped green porridge with crab entrails, dry wafers, smoked eels, and fiddlers scraped their ropes, tavern owners pumped the beer.”

The Chaloupe d’Or doesn’t really match this Sunday morning bacchanalia, as it’s only me and another family, and they eventually leave. I am left alone at table 109, warmed by a fire burning away in the centre of the room, reflecting its flames against the windows and lacquer-glass lampshades. A stray electric extension cord hangs by itself next to a window.

Time, and alcohol are catching up with me, so it is onwards to my next stop on this crawl. To be continued in Act Two, wherein the narrator has a date with Baudelaire’s hairdresser, relives Charlotte Bronte’s opium trip in a Brussels park, and emerges into the 20th century among the Flemish literati.