Drinking in Ganshoren // A cabaret of the unreal

A man walks into a bar, followed behind by his daughter. They exchange a few words in muttered French. A couple ahead of them – man with his arm in a sling, woman fussing over the drinks menu – order their beers in Dutch and take a seat at a rickety wooden table. This is La Charnière, a rudimentary café housed in an 18th century Brussels farmhouse.

The father turns to the man behind the bar and in stilted Dutch says: “One beer for me, but I don’t know any of them on the menu…Ah, they are from Brasserie de la Senne. A Jambe de Bois for me then.” The barman pulls a bottle from the fridge and replies in Dutch: “Take a seat, I’ll bring it over.”

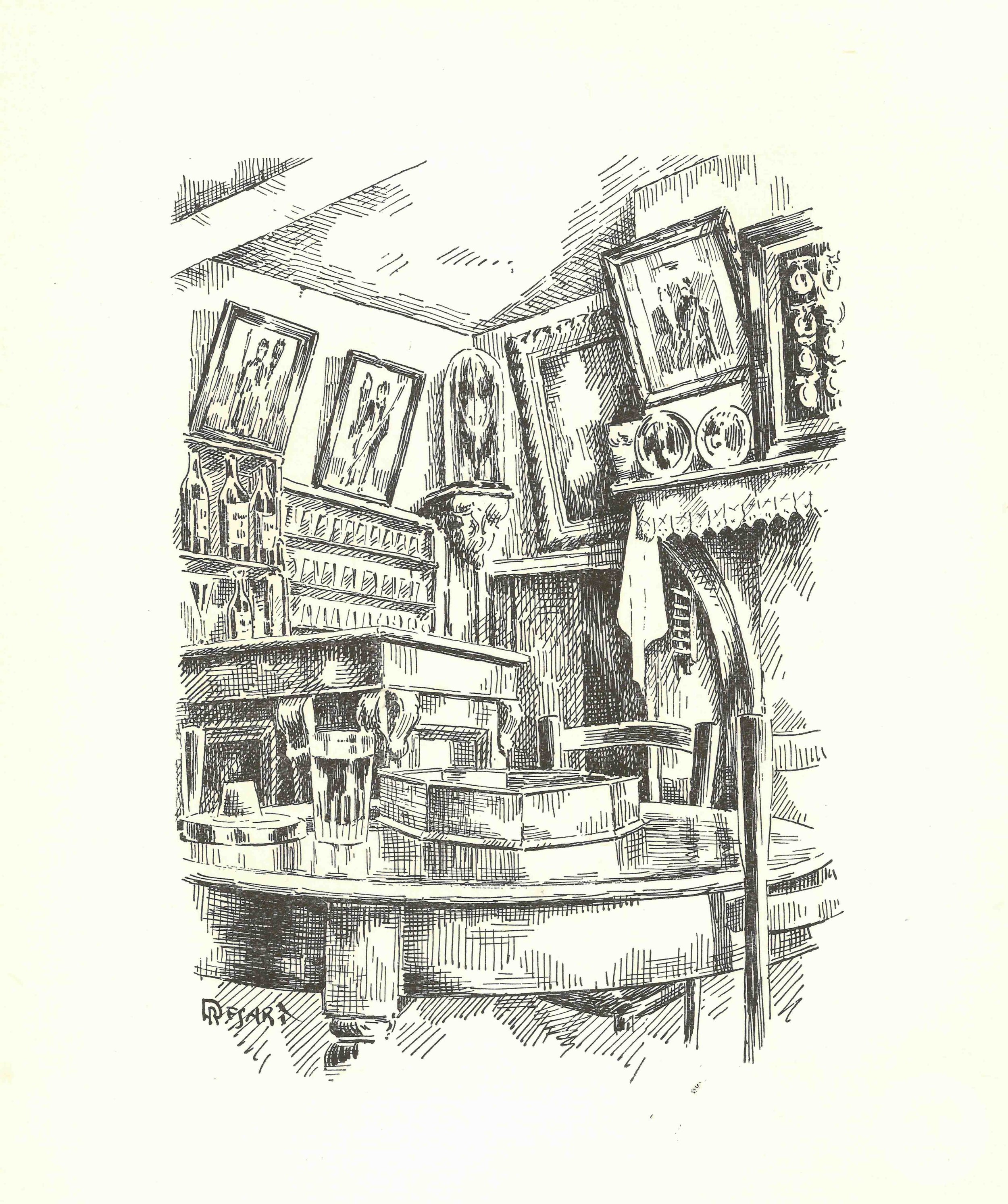

The flotsam of old brown bars

La Charnière, in a side-ally off a roundabout in Brussels’ Ganshoren commune, is a well-worn place. League tables from some forgotten sports club hang on whitewashed walls. Modern necessities – a black speaker box, the odd fluorescent wand – have been bolted on to the farmhouse.

The faded glory of old pigeon fancying trophies, frameless pictures of Belgian royals, a pricelist offering a glass of Duvel for 40 Belgian Francs; this is the flotsam of old brown bars. Someone fires up an old record player; a scratchy, jazzy piano plays. I take a seat, resting my back against the wall and my own glass of Jambe de Bois on a mint-green Campbell Scotch CTS bar towel.

An Illusion

A fairly typical Brussels tableau. It is an illusion. The building is real enough, and the beer too. But there is no, nor was there ever, a bar called La Charnière in Ganshoren. You won’t find this place in any guide book. Because it doesn’t exist. Not really. The pigeon fanciers and their trophies, the royal portraits, they belong not here in Ganshoren but at some now-disappeared kroeg in Schaarbeek.

This “La Charnière” has been has been installed in old auberge-ferme (farm-hostel) in an ephemeral attempt to evoke a folk memory of a rural Ganshoren huddled around farms, farm-cafes, and roadside inns. Places like La Charnière once dotted this part of Brussels, roadside inns, farm-breweries and meeting places for the rural locals. Few remain, and the ones that do – like Au Vieux Spijtigen Duivel in Ukkel – have comported themselves according to contemporary fashions.

The Cabaret - "a machine that works"

In the rural hinterland of Brussels before the 20th century, the typical farm-hostel or cabaret was “a shop where we buy drinks to go, or to drink, or to eat as well”. Brussels poet and journalist Camille Lemonnier wrote a vivid evocation, in 1888:

"Nothing is more curious than these little restaurants: almost all of them extend into a narrow casing under a low ceiling, painted with smoke, with a corner for the counter; the largest would hold barely thirty people. It is necessary to wait, standing up, that a table is bald; still it is not sure to occupy it alone for a long time, because the arrivals invade it at each end. (...) The sink, the kitchen, the room lie on the same plane, through a mist of vapors rising from the pots; and the smell of the furnaces spreads among the consumers, by hot and continual puffs. No coquetry of crockery or silverware either; the plates are placed in front of you, with pewter cutlery on a raspy napkin; the public is considered by the caterer as a machine that works and that it is not necessary to attract refinements.”

La Charnière, or In t’Oude Patchof (the old farm) as it was actually called, was built in 1792 as a farm and eventually converted into an auberge-ferme. There were many auberge-fermes like it in the time before Ganshoren was integrated into Brussels and its rural heritage erased.

The most iconic of them was the Heideken.

The Heideken - "tasty toast with cottage cheese"

The Heideken was a farm-cabaret facing out onto a village green that is now called Square Centenaire. Not a Liza Minelli, nazi-busting cabaret, but a place where the innkeeper offered “the townspeople who visit him large and tasty toast with cottage cheese” or “succulent ham omelettes, the fagots sprinkled with a glass of gueuze or kriekenlambic.” It was home to the local guild of archers, and served for a time as a makeshift town hall when Ganshoren was yet to build its own.

Robert Desart in his 1950 tour through the vieux estaminets of Brussels called it “one of the oldest, no doubt, of the Brussels agglomeration” fighting against the urban cleansing that followed the spread of the city outwards.

Desart’s fears about the threat of urban expansion were well founded. The Heideken lasted only two more years. On July 1, 1952, it was demolished. In its place came a new tramline destined to transport visitors to the Universal Exposition of 1958, away up the hill on the Heysel plateau. Less than 20 years later that tramline was itself demolished; the car was now king.

A Potemkin Village

This urban transformation wrought on Ganshoren unmoored La Charnière from its surroundings, abandoning it on Rue Victor Lowet in a Potemkin village of period buildings in a commune itself detached from its own past and sense of place. When La Charnière invites people from Ganshoren in to appreciate the legacy of places like the Heideken and In t’Oude Patchof, the experience is surely as alien to them as to someone like me passing through. Like the fixtures and fittings of La Charnière, the people in Ganshoren are not from here.

This “here” is now little more than a per-urban stopgap of apartments and roundabouts between Brussels and its Flemish hinterland, home to what the Brussels director and writer Marc Didden called “extremely happy people, because they are, as they say in French, really ‘sans histoires’.

“Remember that you are in one of the few places in the world where nothing ever happened,” wrote Didden.

Tell that to the innkeepers and the urban planners. They are busy again at Square Centenaire. Across from a bar declaiming itself the “New Heideken”, a new tramline to bring commuters away up the hill to the Heysel plateau.

This is part of a semi-regular drinking tour of some of Brussels' less well-known, peripheral neighbourhoods. You can read the first entry, about Koekelberg, here.